Still Spoken

Still Spoken

Can Social Media Companies Profit off the Data of the Dead? with Carl Ohman

Do the dead live forever on social media? If so, how might the social media companies exploit their memories - AND the data of the living? The citizens of the modern age have handed over responsibility for the dead - and culture, and history - to the powers of social media and the market. Why does that matter?

Still Spoken explores how the dead live on: through us, through our stories, and through technology. In this episode, Elaine Kasket, author of All the Ghosts in the Machine: The Digital Afterlife of Your Personal Data, has a fascinating conversation with Carl Ohman. Carl is a recent PhD graduate from the Oxford Internet Institute, the 2020 recipient of the Scotus Early Career Researcher award for Arts and Humanities. He's predicted the tipping point when Facebook becomes a digital cemetery - with more dead profiles than live ones - and more recently he's raised alarms about the dire consequences if Facebook fails.

Carl and Elaine talk economics, equality, politics, history and technology, and how it all links to the digital dead.

Host Elaine Kasket is a psychologist, storyteller, and author based in London. She's an expert in bereavement and in death & the digital. Her latest book is All the Ghosts in the Machine.

Produced by me, Elaine Kasket. I do this podcast ALL BY MYSELF with no production team, editors, or help from anyone other than my wonderful guests. If you want a simple, easy start to your own podcast, you can do what I did: get a great podcasting platform (see the link for mine below) and easily add music and sound effects with an affordable subscription to Epidemic Sound.

Music and sound effects all purchased under license from Epidemic Sound:

Savannah Nights - Zauana

Computer Wiz - Marten Moses

Ga$ Money - Xavy Rusan

Erudition - Ambre Jaune

My Machines - Real Heroes

Rather Erratic - Benjamin Rice

Get to know Elaine's writing on Substack and Medium.

Still Spoken Ep3

[00:00:00] Elaine: I'm Elaine Kasket, and this is Still Spoken, a new podcast about how the dead live on through us, through our stories ,and through technology. Today, I'm talking to Dr. Carl Ohman, whose research at the Oxford Internet Institute concerned a very new phenomenon with very old roots.

Carl: This story really begins thousands of years ago in what anthropologists call deep time, the deep time of the dead

With the nomad, someone dies, you leave them in the sand. You leave them behind, [00:01:00] literally, and you keep on walking.

As we started building the first permanent settlements, you have this problem with, what do you do with dead people? Where do you put them? Suddenly you have to deal with them, and whether you like it or not, they will continue to be present among you.

One of these groups that went from nomadic to permanent settlements is the Natufians, and this really interesting burial customed emerged among them, where they would bury the dead underneath the very houses in which they lived. But also, they would remove the heads of the dead and remove all the flesh [00:02:00] from the skull and replace it with plaster, and then decorate it with the seashells. And then they would keep the skull within the house above ground, among the living. So after a couple of generations, the Natufians would literally, in their homes, be surrounded by the skulls of generations of ancestors.

These houses were usually built out of clay. So we say that they're permanent structures, but really they wouldn't maybe last more than a couple of generations. And then you would collapse that structure and build a new one on top of it. So not only would you build your house literally on a grave, but you would build a house upon a house upon a house, until these were mounds. You were living with the past underneath you.

[00:03:00] Elaine: The Natufians lived in the Levant between 15,000 and 11,000 years ago. And here, Carl and I sat, both of us experts in death and the digital, talking about them. What connection could there be between them and us when it comes to the role that the dead play in our society today?

Carl: When we hear about this strange custom, it feels quite alien to us, but that's because we're making such a big jump. But this custom developed over time, and these skulls would be replaced with more symbolic representations of the data.

In Rome, in aristocratic households, masks were made from imprints of the faces of the dead that you would actually have in your house. In medieval churches, the dead were among you in the sense that they were buried [00:04:00] inside the church. There are reports of how medieval churches would smell terribly of rotten flesh because the dead would be rotting inside the church.

And if we look to the 19th and 20th century, instead we have photos of the dead inside the house. But all of these ways of containing the dead have been, well, containers. There's a frame around the photograph, and we keep the dead in archives and photo albums, or at least we have been doing.

With the digital revolution, once again, we're living within the same structure. We all now live in and through the archive. We're once again, on, in the same matrix as the dead. We're all in the internet.

[00:05:00] Only like 15 years ago, or 10 years ago, you'd say that you're 'going online'. Well today, I mean, I don't think I've heard anyone say that they're 'going online' or that they 'were offline' for at least seven or eight years, because we were always online. We live in the internet. Inside the internet.

Elaine: Now, when I go on my phone, I'm connecting with living people on there, but also staring back at me from the glowing surface of this phone are dead people as well, dead people I knew, dead people. I didn't. They haven't got seashells for eyes. In fact, they're a lot more rich and vivid and developed than that. A lot of us, over the course of our lives, build up a substantial amount of what some researchers have called [00:06:00] 'digital flesh'. And digital flesh sticks around.

Carl: You know, and I think, you know what you're referring to with this sort of ritual of going online. I mean, that's kind of analog to the ritual of going to the cemetery or the ritual of going to the archive. You're sort of visiting the past in a specific site, which you can leave at will. Well, the difference now is that you never leave.

I guess you're, you're always connected and increasingly, so. I mean, you know, just take, take me as an example. I have this device, I'm a diabetic. So I have this device on my arm, which causally sends information about my blood sugar to my phone, which is registered in an app, [00:07:00] which, you know, keeps all this information on a server somewhere. So I am literally like biologically connected to the internet all the time and I cannot turn it off.

Elaine: The other thing that fascinates me about the correspondence with the Natufians is that here they were, and they were saying, okay, this is what we do with our ancestors. We take these skulls and we strip the flesh from them, or we make the plaster mask and who display these in our homes.

But you know, it's not really us that have set out to do that and to shape and preserve our personal dead. In that way, there is a major player taking the decision: this is how we preserve and display our, the dead in our society.

Carl: Often when we talk about new technologies, we, you know, we tend to talk about it as if these technologies just emerged.

Suddenly there was an internet, suddenly there was a Facebook. And we tend to forget the people behind these [00:08:00] technologies, that these are actual artifacts that someone has created for a particular purpose. And that goes for the digital afterlife technologies as well. That kind of stuff that makes us present after our death online. And we ought not to forget that the purpose in, you know, 99% of the cases of these services. Whatever they may be is to make profits.

Elaine: They're not humanitarian organizations. They're not historical archives. They're not philanthropic organizations. They didn't even set out to be legacy [00:09:00] platforms or digital cemeteries. That's not what they're there for, of course.

Carl: And, and look, that's not, that's not a moral critique. That's not saying like, oh, you know, People working in social media need to take into consideration other values than the profit. I mean, if they do, literally, they fail. That's how markets work . Markets only appreciate one type of value: that's profit. And I often get the response of like, Oh, but surely for-profit firms care about other values than profit. And I'm like, well, if they do, they can only afford to do so in so far as these values can converge. That's the name of the game.

Elaine: Well, for the uninitiated, 10 years ago, 15 years ago, when [00:10:00] I started looking into all things, death and digital, there were stories in the news now and again like, Oh, Facebook, we're getting pokes from dead people or invitations related to dead, people's wishing dead people happy birthday, et cetera. And they'd be sort of presented as these freaky deaky kind of news - weird stories.

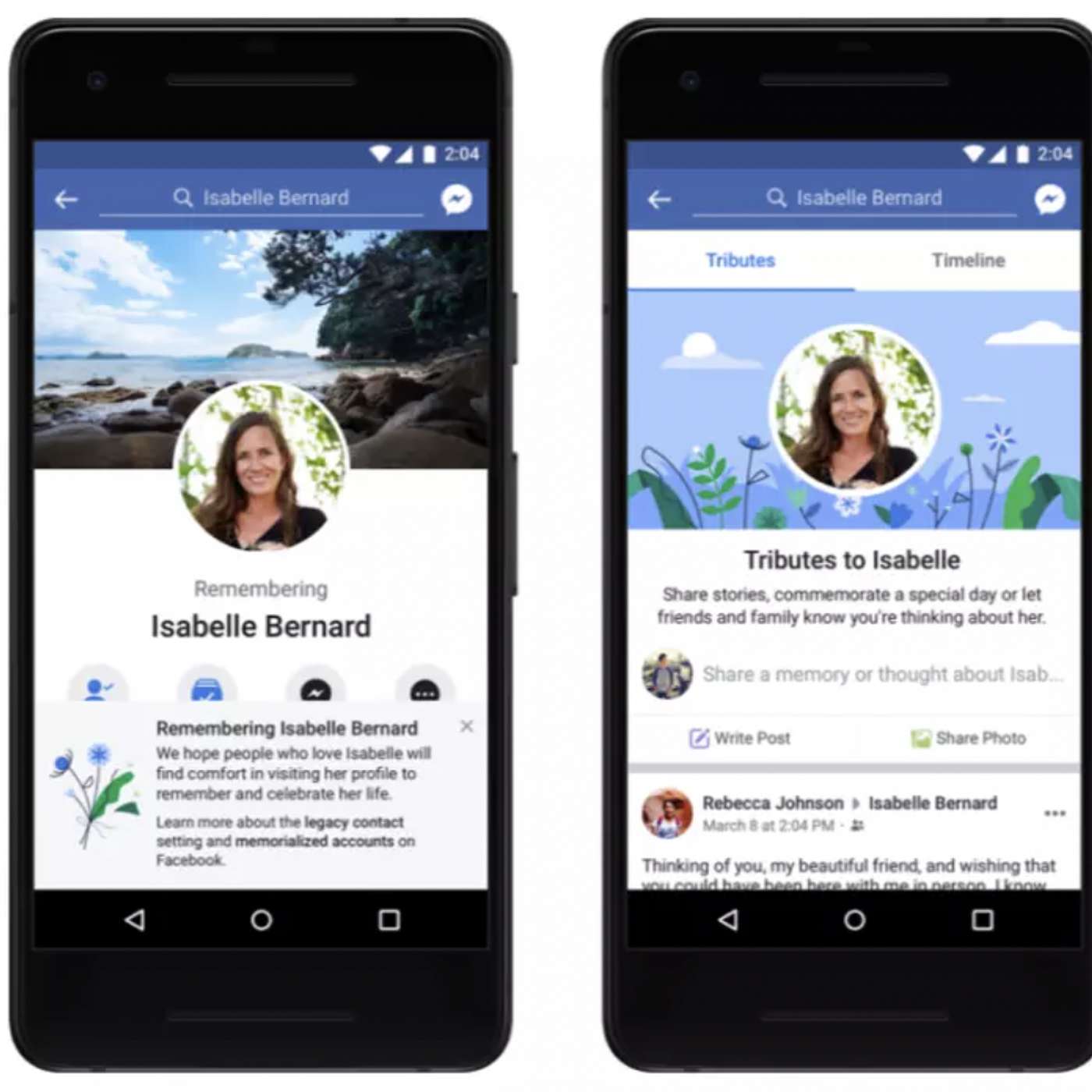

And now though, we're in a situation where almost everybody I know has at least one experience of somebody that they care about, that they're connected to online, who has died and whose digital remains stick around. And in the beginning, social media companies didn't consider that to be their concern. They had delete upon death policies. That was what was in the terms and conditions. And it was only later that memorialization came about. It's really Facebook that has done the most visible work with this, with respect to memorialized profiles and the [00:11:00] tribute tabs, stuff that has to do with what do we do with the data or the information or the profiles of the images, the digital flesh that dead people leave behind.

So basically the mounting data of the dead on the servers of the world has become such a dilemma, and social media companies have taken the lead shaping or determining: this is how we do it. This is what happens with the dead. This is how we preserve their stuff. This is how it's displayed in our digital houses, that is, our phone or our computers. They're steering us on this. And that's a pretty interesting thing for these for-profit companies that are created to other purposes and have their own concerns to take that kind of role on. Talk to me about your thoughts about that.

Carl: Yeah. I mean, it's a really interesting development. We're seeing increasingly how these global tech giants. [00:12:00] are appropriating societal functions that we would previously have seen, I mean, within churches, for instance. So the church would be the mediator. We take care of the death business.

Elaine: And the role of funeral directors, which became a more and more developed role as the 20th century progressed. It wasn't just about burying bodies anymore. It was all about the smoothing over and looking after the experience and selling the coffins and upselling the funeral service...a business as well, a financial concern, but one that explicitly set out to say, We're in the death work business. That was always the basis of their profit. But here's a situation where people who didn't set out to be in the death business find themselves in the death business.

Carl: Yeah, of course. I mean the, the obvious objection here is that I think Facebook has actually done a pretty [00:13:00] good job in de commercializing the interaction with the dead. So they're removing ads from memorialized profiles, which is good, but I mean, there's another side to this. We do feel a connection, or at least traditionally have felt a connection, to churches and to the soil where the dead are buried and so on. But what we're seeing now is that the dead are not buried in soil. You don't feel that sort of attachment and sense of belonging to a particular land or a particular church or anything like that. But that sense of belonging that, you know, contact with previous generations that happens increasingly on social media. Not only are social media shaping our relationships to each other and to the dead as individuals, but they're also shaping our relationship to the societal past as such.

They're shaping our relationship to the [00:14:00] previous generation, the generation that is now filling up Facebook with, with their digital remains.

Elaine: Unless something changes about how management or access to accounts can be handed down. Because the example, you mentioned Facebook, they've got this legacy contact system, and while you're alive, you can appoint a legacy contact to say, I want this person to be able to perform some management functions on this account after I die, this profile after I die. But as far as I know anyway, is there's not a further hand-off mechanism. So that, that person's, you know, grandchild's or great grandchild can also access the profile that represents the ongoing digital body or digital flesh of the ancestor. You know, I can go and visit the land in which my grandparents and great-grandparents are buried. But my daughter, her kids wouldn't be able to see [00:15:00] anything that I posted on my Instagram or Facebook or whatever today - there's not that same kind of continuity. And I wonder what the consequences of that are.

Carl: You're raising an interesting point here that you can't, there's no legacy contact of the legacy contact. Which is, I think very it's telling for how the tech community deals with this kind of issue. Both academics, actually, and people in the industry, they tend to deal with problems on either a very short term basis, such as like, well, what's going to be the next big technology leap in the next five years, which is code for what's worth investing in. Either that, or it's like, what's AI going to be like, you know, 150 years from now, you know, is AGI gonna take over the world. And [00:16:00] so on. And rarely do you hear discussions of like, well, what's, what's the internet going to be like in 30 years, 20 years? It's very much within our lifetimes. We'll be the same people, but it's too far away to be commercially or economically relevant to talk about that kind of a scenario. I mean, there are literally going to be where there's a good chance that there are going to be more dead than alive users on Facebook. We're talking about hundreds of millions or billions of, of profiles, of deceased users. We were quite shocked to see that if they would continue to grow. Uh, there were to be close to 5 billion deceased profiles of deceased users by the end of the century.

Elaine: Which fundamentally changes the nature of the site, and its incentives to keep going, [00:17:00] for a company that in its current business model derives about 98.5% of its revenues from advertising.

And as you say, they have done a good job of keeping the advertising side of things off of the memorialized profiles of deceased users. What a fascinating encapsulation of what you're talking about at the beginning about the dead sticking around and populating, in greater numbers all the time, the same digital spaces and places that we all pace through and inhabit and communicate through every day. That's the most visible presence the dead have ever had in our societies.

Carl: Yeah. And I think we're challenged as a generation with both the ethical and political questions of what are we to do with this presence, you know, what are our responsibility, both to the current generation, but also our [00:18:00] responsibility towards the dead and our responsibility towards future generations. Do we owe future generations to, to preserve and, and curate and steward this gigantic digital heritage, because after all we've never had such a big archive, such a gigantic archive of human behavior.

Elaine: With potential to use it for good. Use it for ill. Use it for profit. Use it for the betterment of society, all of the above. So there's about four ethical stakeholders that you outline in your research. And one of those is a future generations. One of those is the deceased entities themselves, which don't have sentience. And which haven't historically anyway, had legal personalities are considered to have a stake, but now we're starting to wonder now that there is so much digital flesh that we build up, we're sort of thinking, okay, wait, what is our responsibility to these deceased entities that stick around in these [00:19:00] spaces, then there's the current users.

And then there was a fourth one that I'm forgetting. Ah, yes. Dependent communities...and you know, we're sitting here we're I know I'm in the UK, you're in Sweden. We have access to a different kind of internet than they do. For example, in Thailand and Laos, in countries where, uh, partly through Facebook's initiatives to increase access, a hundred million people that wouldn't have otherwise been online are online because of Facebook's initiatives in those developing countries.

The result of that, of course, is in those places, Facebook and the internet are pretty much synonymous with each other, all of the kind of communication and the functions that happens societally are facilitated online, are happening on Facebook.

Carl: Now, I was just going to add upon that, that I think that touches then onto the broader point of often the way we talk about technology and the various challenges and [00:20:00] dangers that arise from the technological development...we tend to equate these dangers with who are using the technologies, who are dependent on them directly as individuals. But I think that's an incomplete analysis, because you ought to be concerned with what happens to Facebook's data, even if you're not on Facebook, because that data could be used, could be sold, and that could in turn be used to analyze your behavior.

Elaine: It's this conceit that we have like, Oh, well, you know, I don't do social media. I am therefore unaffected by social media and essentially part of what you're arguing that you're like, hello, wake up. None of this is unaffected by social media because now it's so much a part of the fabric of society that even if you're not on it, it matters to you.

Carl: Let me provide a couple of examples. [00:21:00] So an example which few people I think consider is a scenario in which Facebook goes bust. So, you know, there there's a Facebook bankruptcy, and there's no more Facebook. What happens to Facebook's data? Well, it's like, like in any bankruptcy basically, or any insolvency case, uh, the assets are going to be sold out to the highest bidder

Elaine: And on Facebook, what are those assets, Carl?

Carl: Those assets are the servers with all the data of 2.7 billion people.

Elaine: How is, or why is that data valuable? Who is it? That is queuing up, just bid for the data that Facebook might sell off if they have a fire sale. And why is it valuable?

[00:22:00] Carl: Well, I mean, the scary answer...the scary answer to that question is anyone. I mean, anyone can basically buy it that has an interest in an interest in it...anyone can buy it.

In the GDPR it's somewhat regulated, in that only businesses within the same industry. So it would be another social media company that would acquire it.

Elaine: So GDPR says that - the general data protection regulation in Europe- stipulates that, okay, if a Facebook has to have a fire sale and all this goes up for grabs, it's only another type of company that can sort of buy it. So it says that on the face of it, you know, there are...

Carl: It has to be a social media company or like a similar business. So the Russian government can't be like, Oh, you know what, guys we're buying that. But for people who are not covered by the GDPR, like most of the time...

Elaine: Which is most of the world.

Carl: Even if your data is not on there, this matters to you. Because your parents’ [00:23:00] data might be there. Your parent's, parent's data might be there, your sibling's data, or your friend's data. People who live in the same house in the same community. And the thing with data is that it works kind of like genetics. So. I may not need your individual DNA in order to tell something about you. If I have your parents' DNA, I can actually draw a lot of inferences from that about you and the same thing with data. If I can analyze people in your proximity, I can actually make a lot of references about you as an individual. The data of the dead, it's not just a concern, uh, is not just a niche concern, but it's very much epicenter of the privacy debates. It's it's, it's a very mounting central issue that we're going to face in the next couple of decades, which is why we need to start talking about it now already.

Elaine: Here's another illustration of how that, not just the data of the [00:24:00] dead, but also the data about the dead can make a difference in exactly the way that you described.

So here's all these people. Genealogy is the number two most popular hobby in the United States. It's pretty high up there in the United Kingdom. We love researching our family history, and what a miracle it is that modern science enables us to spit into a tube and post it off with a code and surrender our biometric data to a company like Ancestry or 23 and Me. And I might think, Oh, well, how on earth does it affect my sister? If I send off my DNA, well, it affects my sister because my DNA is also information about my sister. And if I log all of this information about my family history and attach photographs, from the shoe boxes my mother keeps in the basement of previous generations, and tap in all the years of birth and death and everything like that to make my family tree on ancestry... this seems like fairly harmless pursuit of an interesting hobby that gives my [00:25:00] life meaning and shape. And where did I come from? All of that malarkey. But it actually captures kind of a lot of information about previous generations and current generations that then connects to still living individuals and has implications for them as well.

And just like DNA, like you say, genetics...on the internet, everything, and everybody is connected. Not for nothing do they call it a network.

Because the thing that you mentioned just now about Facebook going bankrupt, people might think no way, the behemoth is too big to fail. Just this week, the Federal Trade Commission and 48 attorneys general in the United States mounted the first antitrust assault on Facebook from within home soil.

After a raft of things from other countries, the United States. It's finally pulling together an antitrust lawsuit against Facebook. The Financial Times argued that the Biden administration [00:26:00] incoming is likely to be aggressively in favor of this because Obama's administration, let things get kind of out of control with some of these big tech companies

it's arguable that Facebook is being given a run for its money more strongly than ever has before. Uh, which brings us closer to the kind of scenario where. Facebook. Yes. Even Facebook could fail or significantly change and its business models and what could happen to all of our data then?

Carl: Definitely. It's, it's again, we, we must not look at only this kind of five-year short-term perspective, but rather look to the horizon of what might happen 10 years down the line or so, because revenue models change, user behavior changes. And so on. And so I see this as one of those rare, super interesting cases where regardless of what happens, if Facebook keeps its hegemony in society and [00:27:00] becomes this global Colossus, which just influences how we view the past, how we communicate, like regardless of whether that happens or whether it goes bust, the implications are super interesting.

Elaine: I’m sure you saw, in November of 2019, Twitter announced that it was about to commence a big cull of inactive accounts. Uh, they said, Oh, in December we're to, uh, cull all of these accounts. So if you haven't logged into your Twitter in a while and you still want to use it, make sure and login.

And of course that's always been in their T's and C's, you know, it's good for them to get rid of accounts that are inactive, but it also amounts to a delayed delete upon death policy because dead people don't tweet. So a lot of bereaved people really kicked off and they said, Twitter, you can't do this. You can't delete my father's, my brother's, my cousin's, my favorite author's Twitter. And within [00:28:00] 24 hours, Twitter had backtracked and said, sorry, sorry. Didn't mean to, we hadn't thought about this, which seems odd, but we'll look into memorialization policies like our friends over at Facebook and Instagram.

And my reaction to that at the time was like, no, like, wait, stop. You know? Cause I'm just really aware of this like force towards memorialization, not just in terms of their company's willingness to do this, but our expectation that they ought to, that they have some sort of obligation, like a moral obligation to preserve the data of those that are gone and we've gotten to that place really quickly.

Carl: Yeah. Yeah, no. And I was just going to comment on that, that my, my prediction is that this drive towards memorialization is not going to last...at least it's not a sustainable solution. As you pointed out before [00:29:00] dead people don't click on apps. They're they're worthless from, from a commercial standpoint, unless they can be used to tie new users to the network. So, you know, I I'm still on Facebook because my, my dad's, grandmother's account is on there and I don't want to lose touch or, you know, I created a twitter profile, so that I can keep in touch with, uh, you know, my dead uncle on there.

I'm, I'm doubtful that this is actually going to be financially viable because you know, sure. It works now. You have, I don't know, maybe a hundred million dead profiles or a couple of tens of millions, but in a couple of decades, those are going to be hundreds of millions or billions of profiles who are going to be on there. And remember that those we have still take up so much [00:30:00] server space. Those will still be a pretty big cost to administrate. So sooner or later, my anticipation is that social media companies are going to have to choose: who do you preserve? Who gets to be memorialized? And there are all kinds of models for that, but at the end of the day, I think the principle that they're going to go with is, well, it's someone going to pay for this profile to stay up, kind of like you paid for, for, for a spot in the cemetery. And you'll have that for, I don't know, you know, a generation or two and pay for it. Well, the problem of course, is that that's going to feed into various, I mean, all kinds of economic inequalities, I assume that there's going to be a standard price for that, you know, and now I'm speculating, but eventually this is going to become a necessity.

And I assume that there's going to be a standard price. Let's say, you know, $5 for so-and-so many years. [00:31:00] Well, $5 is maybe not a whole lot to most Americans, but it's a whole lot if you go to, like Mali.

Elaine: You've already got that model. One of the things that I wrote about in my book was individual funeral homes that say, Oh, you know, to preserve this archive for this many years, for this many years, and there's like a list. Of tariffs of fees, you know, that it takes. And, okay, so that's an individual situation, individual funeral home. When you're talking about the hugest database of humanity ever, and you think about all the existing ways in which data and the way data is handled already contributes to inequalities, the algorithms of oppression, the kinds of ways that decisions now...what happens to whose data, what is foregrounded and what is backgrounded and what is deleted? What is preserved? There are values in those decisions. You know, that that [00:32:00] is prioritizing of certain people, certain communities, certain views. So many of our societal ills might be connected to the fact that we remember and listen to and rehearse the history of the victors and the dominant civilizations as the rich and the people who were able to pay for their memories to be preserved and the voices and the experiences of the downtrodden, you know, these invisible masses of people who are no less important, but whose experiences we've been free to forget. Because they've been overlaid because history is written by the victors and it'd be the same thing...the democratizing potential of the internet is kind of undercut if you eventually come around to the same place where you're like, Oh, only these people are preserved. And these are the values that go into that.

Carl: It is the same thing, but I would just want, I would just want to emphasize one crucial difference, [00:33:00] which is that the reason that history up until now or historical records have been so skewed. I mean, we basically just, when we talk about history, we basically just talk about the history of like rich white men, basically.

Elaine: Like the people in charge in Silicon Valley.

Carl: Kind of! But I mean, historically those have been the people who were affluent enough and powerful enough to record their thoughts in their lives and maybe have their portraits painted and whatnot, but at the time recording was expensive. So, you know, if you're going to have your portrait painted, you better have some surplus money to, to, to do that with, we'll tell you, we're almost in the opposite position. That recording is the standard. It's the default. I mean, we, we record everything. Everyone is recorded as soon as they pick up their phone. Which means that before in, in history, we've asked a question, is this [00:34:00] event, this person important enough to record? Whereas today we ask the question, is this person or this event unimportant enough to delete. So we've flipped it around. We have, we have this amazing opportunity to actually create a more diverse and just history. Um, but if profit is the only, uh, principle of how we select what data survives well, we're, we're gonna just gonna repeat the mistakes of the past.

Elaine: So much of the responsibility for information. The shaping of information, the preservation of information or not is sitting in the hands of these handful of major players. You know, GAFA. Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon. Those are companies [00:35:00] for whom profit is at the heart of the matter. And so it feels, it feels scary, partly because I guess there's just such fundamental questions already about the problematic nature of some of the way information is shaped or is corrupted or trustworthy or untrustworthy on these platforms. And...to then think about that being the record that goes forward feels really tricky.

Carl: Yes. And I mean, in my critique again, you know, I really want to stress this, that it's not a critique against these companies or these firms that they're doing something wrong. The critique is rather political. It's a critique against us as a society.

That we have allocated this super important question of how and what do we preserve [00:36:00] completely to the market. We really should have a discussion of what principles ought to guide our preservation of the past. But instead of opening up that discussion, we're saying, well, there should only be one principle and that's the principle of profits.

And I think that's that's because we were not accustomed. To thinking about digital data as historical material, because still the internet is viewed as this new contemporary thing. But as we go along, we need to start recognizing that digital artifacts actually have a huge cultural heritage value.

Elaine: Yeah, and they are more fragile or more vulnerable than we imagine.

Carl: Yeah. It's like that quote about digital data. [00:37:00] Digital information lasts forever or five years, whichever comes first.

Elaine: Its existence doesn't mean that people who care about it necessarily have access to it. The idea of handing over responsibility to Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Google, they're shaping our relationship with previous generations and with history, these entities that are such complex actors in our modern day age, I don't feel good about relinquishing that responsibility, even that even death, even grief, even memory, even history.

Carl: I get the question a lot of like, okay, so what should we do? What's your policy proposal? To be honest, I don't really view it as [00:38:00] my role as a researcher to tell people what to do to find like solutions to problems in society. But rather I view it as my role to formulate problems that we're facing as a society, and then hand them over to our democratic communities being like, look: here's something that we need to discuss. So I think the first step is basically just to communicate, to policy people, to politicians, but also just to ordinary citizens: look, you need to consider this perspective. We need to ask of those questions that you just mentioned. When is it worth breaching the privacy of dead people? What is a legitimate claim? Who should get access, who decides what data we destroy and what we preserve? My response to that is, yes, those are questions that we must consider, and we must take into account multiple different [00:39:00] forms of value, the historical value, scientific, sentimental, and so on that guides that discussion that we must have in our democratic institutions.

But in saying that I am also obviously making some form of recommendation, because what I'm saying is look, this is complicated. We need to take into account multiple different forms of value...that is we cannot allocate this matter completely to the market.

Elaine: I'm Elaine Kasket, and in each episode of Still Spoken, I'll be examining some facet of how the dead live on through us, through our stories and through technology. I have been talking to Carl Ohman, who recently became Dr. Carl Ohman when he successfully defended his thesis at the Oxford Internet Institute. [00:40:00] He is the recipient of the 2020 Scopus Early Career Researcher Award in Arts and Humanities.

If you're enjoying the podcast, please do subscribe. Leave a review and tell your friends. Until next time, when I'll be examining another way the dead live on while their names are still spoken.

.jpg)